AI is shifting from systems that answer questions to systems that take actions. The moment an agent can move money, share data, trigger a workflow, or shape a decision, the question stops being “is it accurate?” and becomes “who is it loyal to, and who is accountable when it acts?”

That is the space I call fiduciary intelligence, which is the discipline of building AI agents that operate as instruments of a fiduciary relationship—loyalty, care, conflict-handling, and auditable responsibility—rather than as clever automations wrapped in disclaimers.

This is not a philosophical add-on. It is emerging as the practical requirement for deploying agents in high-stakes domains without creating a fiduciary gap: a world where a system has power over people’s outcomes, but no one is structurally obligated to be in their corner.

The legal reality builders keep trying to route around

Agency law and fiduciary law exist for a simple reason: contracts are incomplete, power is asymmetric, and principals can’t fully specify what they want in advance. In those contexts, the law fills the gap with duties—especially loyalty and care—so the agent doesn’t exploit the discretion they were given.

For AI agents, a useful framing is risky agents without intentions.

They can act “on behalf of” people and organisations, but they don’t have mental states. So the legal system evaluates them through objective standards (negligence, strict liability, or heightened care in fiduciary-like roles) and pushes accountability back onto the humans and institutions deploying them.

Two implications matter for shipping agentic systems:

- Using AI does not lower the duty of care. Substituting machine judgment for human judgment is not a discount code for responsibility.

- AI doesn’t replace fiduciaries; it operationalises them. In practice, AI systems function as instruments through which human or institutional fiduciaries discharge—or breach—their duties.

If we accept this, “fiduciary intelligence” becomes a design problem, not a legal theory seminar.

What fiduciary intelligence actually is

I use fiduciary intelligence as a concrete standard for agentic systems:

An agent has fiduciary intelligence when it can (1) identify the principal it serves, (2) act with loyalty to that principal’s best interests within the bounds of law, (3) exercise context-appropriate care, and (4) produce evidence that these duties were followed.

This is aligned with the emerging fiduciary AI design procedure: a six-step approach to designing and auditing systems for fiduciary compliance—context, principals, best interests, aggregation, loyalty, and care.

What’s important is the ordering: Most teams start with model choice, tools, and prompts. Fiduciary intelligence starts earlier: who is the principal, what counts as their best interest here, how do conflicts get handled, and what standard of care is required in this context. Only then do you design the agent.

Loyalty is not “alignment” (and care is not “accuracy”)

Builders often collapse these ideas:

- “If the model is aligned, it’s loyal.”

- “If it’s accurate, it’s careful.”

Neither holds.

Loyalty is about conflicts of interest and discretionary choices. A system can be safe and functional and still be disloyal—optimising for platform revenue, partner incentives, or internal KPIs at the user’s expense.

Care is about competence under uncertainty, appropriate diligence, monitoring, and risk controls. It’s not just “the right answer,” it’s “the right process,” with the right checks, in the right context.

This distinction is why professional services are a useful warning signal. As the industry moves from AI-as-tool to AI-as-agent, “human in the loop” can become a legal fiction: the fiduciary anchor erodes if a person is nominally present but substantively absent.

Fiduciary intelligence is the alternative to that erosion.

The non-negotiable constraint: law-bounded loyalty

There is a temptation in agent design to make the system maximally obedient to the user.

A fiduciary frame rejects that.

A credible approach is law-following AI, which is a principle that agents should be loyal to principals only within the bounds of human law, and refuse illegal instructions even if requested by the principal.

This matters because, in fiduciary contexts, “best interests” is not “whatever the principal asks in the moment.” It is a bounded mandate constrained by legal and normative commitments.

If you can’t encode that boundary, you don’t have fiduciary intelligence—you have an accelerant of potentially unlawful behaviour, whether by omission or by commission.

Duties without personhood: accountability without escape hatches

A separate question is whether AI systems should be treated as legal actors with duties.

One emerging approach argues the law can impose actual legal duties on AI agents without granting them rights or full personhood—preserving optionality about future recognition while avoiding premature moralisation.

As a builder, I like this direction for one reason: it keeps accountability grounded.

The opposite direction—rushing toward AI personhood—creates a predictable governance failure mode: shifting blame from designers and operators to the “AI entity.”

In moral philosophy this pattern has a name: agency laundering—obfuscating responsibility by inserting a technological system and letting it absorb accountability heat.

Fiduciary intelligence should be designed to make agency laundering structurally difficult. Every consequential action must map to a chain of authority, a duty-bearer, and an evidence trail.

Corporate governance is already being reshaped by agentic reliance

Take Delaware corporate law as an example: this explicitly defines directors as natural persons. Fiduciary duties still attach to human directors and officers, not to the AI tools they use. At the same time, director reliance is being stress-tested by algorithmic decision inputs. DGCL §141(e) provides that directors are “fully protected” when they rely in good faith on corporate records and on opinions/reports from officers, employees, committees, or other persons believed to be experts selected with reasonable care.

The open question is not whether boards can use AI, but rather how the standards of care, oversight, and “reasonable reliance” evolve when the “expert” is an opaque model, a vendor pipeline, or an autonomous system that can initiate actions.

From a CEO’s perspective, the practical takeaway is simple: If your governance posture is “the model told us so,” you are building a liability story, not a decision system.

Fiduciary intelligence is the antidote that makes reliance on agentic intelligence legible, auditable, and duty-constrained.

Regulation is converging on risk, but duty is the deeper layer

The EU AI Act is the first comprehensive AI framework with a risk-based structure, aimed at fostering trustworthy AI. Risk-based regulation is necessary, but it is not sufficient for agentic systems that act in advisory/intermediary roles. Risk frameworks answer “how dangerous is this system?” Fiduciary intelligence answers “who does this system serve when it has discretion?” In other words:

- risk tells you what to prevent,

- fiduciary duty tells you what you must affirmatively do for the principal.

If we want agents that can operate in healthcare, finance, public infrastructure, and cross-border data environments, we need both.

What this looks like in practice

At IXO we are building intelligent systems for domains where trust is not a UX issue—it is a systems constraint: public health, climate verification, cooperative finance, sovereign data.

That is why our stack leans into verifiability, identity, governance, and shared state.

- PathGen is designed as a federated, sovereign-by-design platform: countries retain control of raw data while sharing analytics and insights for joint decision-making. That architecture is explicitly framed as foundational to trust in long-term regional cooperation. It integrates pathogen genomic data with contextual datasets and uses advanced AI (including foundation models) to surface outbreak intelligence.

- Qi is designed as an intent-first intelligent cooperating system: coordinating people and agents to produce verifiable outcomes using the open, sovereign IXO infrastructure. This has an identity layer (verifiable DIDs), a proof layer (cryptographic proofs of events), a governance/automation layer (smart contracts managing permissions and policy enforcement), and a privacy layer using federated systems and encrypted Matrix communication.

- Qi Flows operationalise governed execution: the Flow Editor lets teams model steps, roles, dependencies, and authorisations, then execute the same model with decisions recorded and permissions enforced.

This is not “compliance theatre.” It’s an engineering answer to a fiduciary question:

If an agent can change the state of real-world systems, can we prove what authority it acted under, what duties constrained it, and what evidence supports the outcome?

A framing from within the Qi architecture is useful here: A real “skill” is defined by changing shared state; if the network state doesn’t change, the “skill” didn’t fire. Fiduciary intelligence is a product, not just a principle that encodes the physics for authority + duty + state transition + evidence.

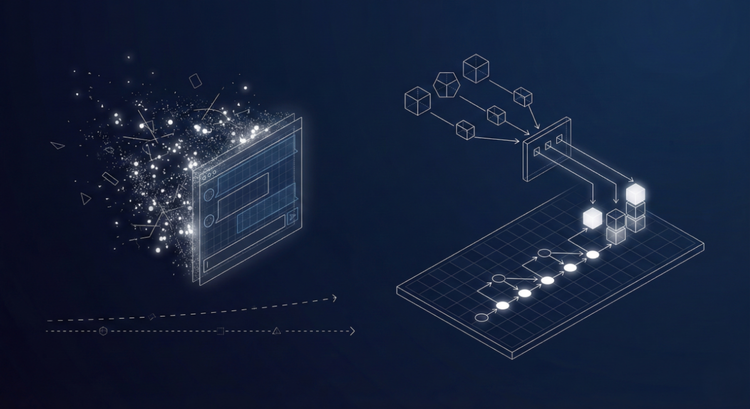

The Fiduciary Intelligence Stack

This is the architecture we reference when building agentic systems for high-stakes environments:

- Principal layer

- Duty layer

- Authority layer

- Execution layer

- Evidence layer

Shipping fiduciary intelligence without boiling the ocean

If you’re building agentic solutions for any domain where outcomes can harm people—these are the fastest moves that compound:

- Declare the principal in-system

- Write a “duty spec” before you write prompts

- Put a law gate in front of action

- Constrain agency through capabilities

- Route high-stakes actions through governed flows

- Make every action a state transition with evidence

- Engineer conflict-of-interest detection as a first-class feature

- Treat reliance as a design object

- Assign an “accountability owner” for each agent domain

- Build for audit on day one

If you can’t reconstruct why a decision happened, you don’t control the system

Alternatives and trade-offs (so you can choose deliberately)

There are at least three competing approaches teams take:

- Contract-and-disclaimer approach

- Product-liability expansion approach

- Fiduciary intelligence approach

My bias when building systems for discretionary and high-impact, is that the fiduciary intelligence approach is the most defensible and cost-effective option because it prevents expensive failure modes where trust collapses, and regulatory liability compounds.