The mismatch between what Agents can do and how to coordinate this in real-world systems is becoming a key realisation of the current “agentic moment”. We’ve learned how to make models talk and call tools. We haven’t learned how to make their actions legitimate, attributable, and safe in the real world.

The agent era is real, but we’re measuring the wrong thing

Most teams still judge agents like they’re chatbots:

- Was the answer “good”?

- Did the tool call succeed?

- Did the workflow complete?

Those are necessary. They’re not sufficient.

The moment an agent changes something that matters—moves money, approves work, updates a record, triggers a contract, alters a model in production—you’re no longer evaluating a response.

You’re evaluating a commitment.

And commitments require governance.

The core failure mode: implicit actions

A lot of agent systems look impressive until you ask:

- Who authorised this action?

- What exactly changed?

- What is now true?

- Who is accountable if it’s wrong?

- Can we reverse it?

- Can we settle it?

When these questions don’t have crisp answers, you’re not running a system. You’re running a demo.

The root cause is simple: most agent frameworks treat actions as side effects rather than state transitions.

The agent “does things,” and we reconstruct what happened from logs, traces, and dashboards after the fact.

That’s backwards.

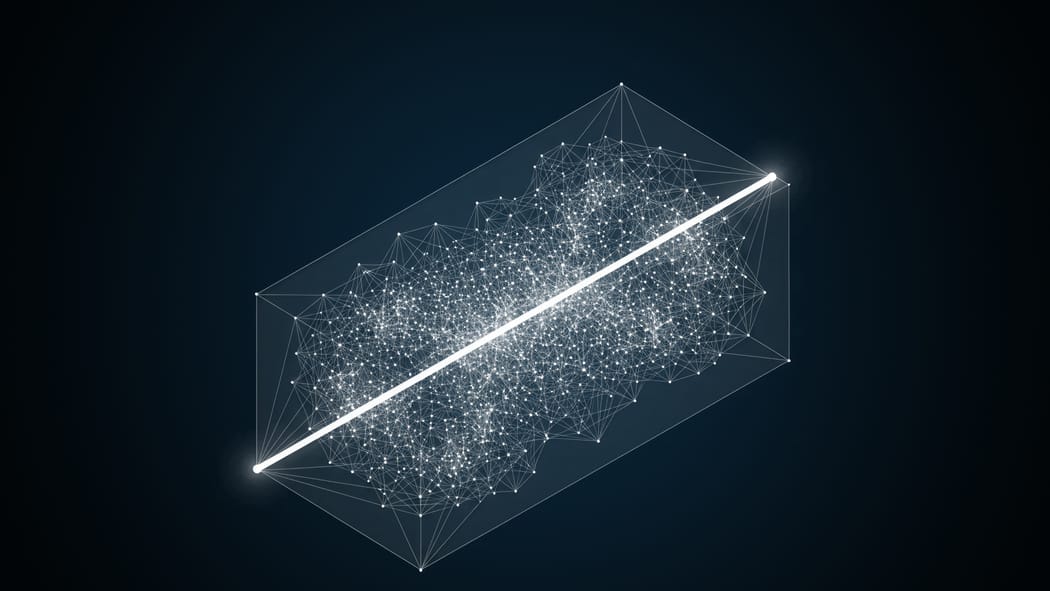

What matters now: transition semantics, not agent graphs

The industry talks a lot about agent graphs—nodes, edges, routing, tool selection, reflection loops.

That’s not where the real leverage is.

The leverage is in explicit, observable transition semantics:

- A shared object is in State A.

- Someone (human or agent) proposes moving it to State B.

- The proposal is evaluated against policy.

- Evidence is attached.

- Approval is recorded.

- The transition is executed.

- The new state becomes the shared truth.

Read this for the foundational case: chat output is not the same as coordinated execution.

When you design agents around explicit transitions, you get three things “for free” that are otherwise painful:

- Accountability: You can point to who proposed, who approved, and what policy allowed it.

- Auditability: You can read the history as a sequence of state changes, not a pile of logs.

- Operability: Rollbacks, disputes, and exceptions become normal system behaviour—not emergency incidents.

From guardrails to governance

Most “agent safety” today is guardrails:

- prompt constraints

- tool allow lists

- content filters

- monitoring and evaluation

Useful, but shallow.

Governance begins when permissions and policy are applied to state transitions, not just access.

Access control answers: “Can this identity call this tool?”

Transition governance answers: “Can this actor move this object from State A to State B, under these conditions, with this evidence, and with these approvals?”

That’s how you run agents in regulated, high-stakes environments without pretending that monitoring is control.

Monitoring tells you what happened.

Governance determines what is allowed to happen.

The missing layer: settlement

There’s another truth most agent builders avoid:

Real work has economics.

If an agent executes tasks, someone needs to be:

- authorised to commission it

- accountable for approving it

- able to verify completion

- able to pay for it (or reverse payment)

- able to dispute it

Without settlement, you don’t have production automation.

You have activity.

This is why so many agent deployments stall at “internal helper” and never become “operational infrastructure.” The system can’t close the loop between action and consequence.

The next stack: cooperation over shared state

Here’s the direction I believe the stack is moving toward:

- Humans define the intent and outcomes, which drive state-changes.

- Models produce candidate actions.

- Agents propose transitions.

- Humans and policies verify transitions.

- Shared state is the coordination substrate.

- Verification and settlement close the loop.

- The system learns from outcomes, not just outputs.

This is the shift from “agents that do things” to “systems that cooperate.”

Not cooperation as a vibe.

Cooperation as a technical architecture: shared state, explicit transitions, verifiable evidence, enforceable policy, and settlement.

That’s what makes multi-agent, multi-team, and multi-organisation workflows actually work.

Where Qi fits in this world

Qi is built around a simple idea:

If you want humans and AI to cooperate, shared state has to be first-class.

That means:

- intent is codified, and linked to outcomes

- work is expressed as state transitions

- approvals are explicit

- evidence travels with the action

- outcomes are verifiable

- payments and disputes are native workflow events

The goal isn’t to build “the smartest agent.”

The goal is to build the most governable cooperation, to achieve provable outcomes.

Because in the real world, intelligence without legitimacy is just risk.

Conclusion

Agents will keep getting easier to build.

The winners won’t be the teams with the most agents.

They’ll be the teams with the clearest semantics for what changes, who can change it, and how the system settles the result.

That’s the state of agents right now.

And it’s where the real work begins.

Three questions to pressure-test your agent strategy

- What are the highest-value state changes in your business, and which of them can you describe today as explicit, auditable transitions (not implied side effects)?

- Where are you relying on monitoring as a substitute for governance—and what failure would force you to admit that’s not control?

- If agent execution becomes abundant, what is your scarce resource: trust, approval capacity, policy clarity, or settlement mechanisms?